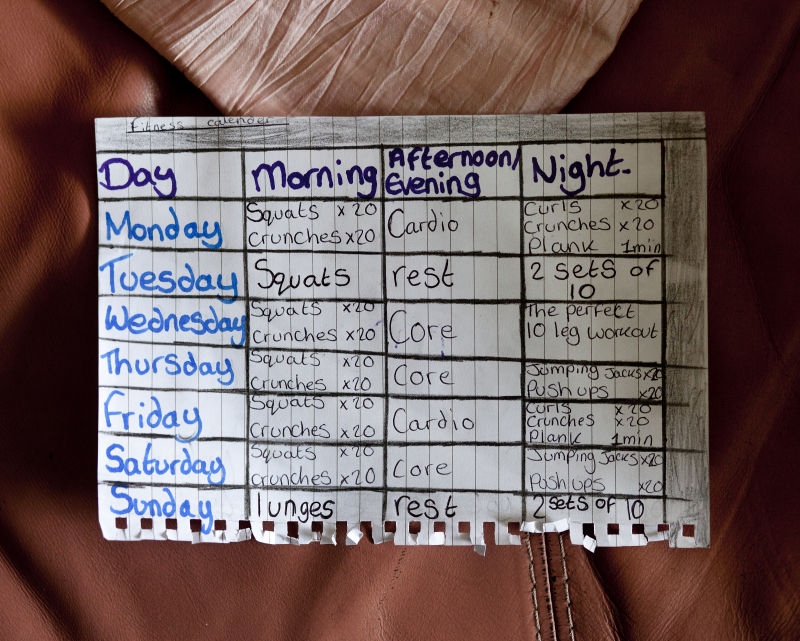

Our teenage years are arguably the most awkward of our lives. Whether it’s acne, depression, body dysmorphia, anger management, or any other number of issues, the turbulence of hormones and physical, mental and emotional changes, all while navigating school.

But imagine having all that going on,

and being fat.

Growing up fat myself, I believed that if I wasn’t fat, then somehow everything else in my life would be problem-free. Obesity isn’t a hidden problem. It’s one that you wear, one that everyone can see. One that makes it harder to run away from, and ultimately harder to address. Yet there are more obese children today than ever before. The WHO estimates that there are now 124 million school-age children and adolescents living with obesity worldwide and that by 2030, obesity will be the single biggest killer on the planet.

These are

shocking figures. In the future more people will die from obesity than starvation.

But alarmist headlines almost always fail to examine the everyday reality of struggling with weight and self-image. The psychological effects of being fat in a society that values thinness, interest me as much as the obvious health impairments. Being overweight or obese is deemed to be self-inflicted, even a lifestyle choice, and the ‘culprit’ labelled, greedy, lazy, lacking in discipline. Obesity has taken over from cancer as the thing to fear, with the ‘Big O’ and its stigma and discrimination following the overweight from the schoolyard into the workplace and beyond.

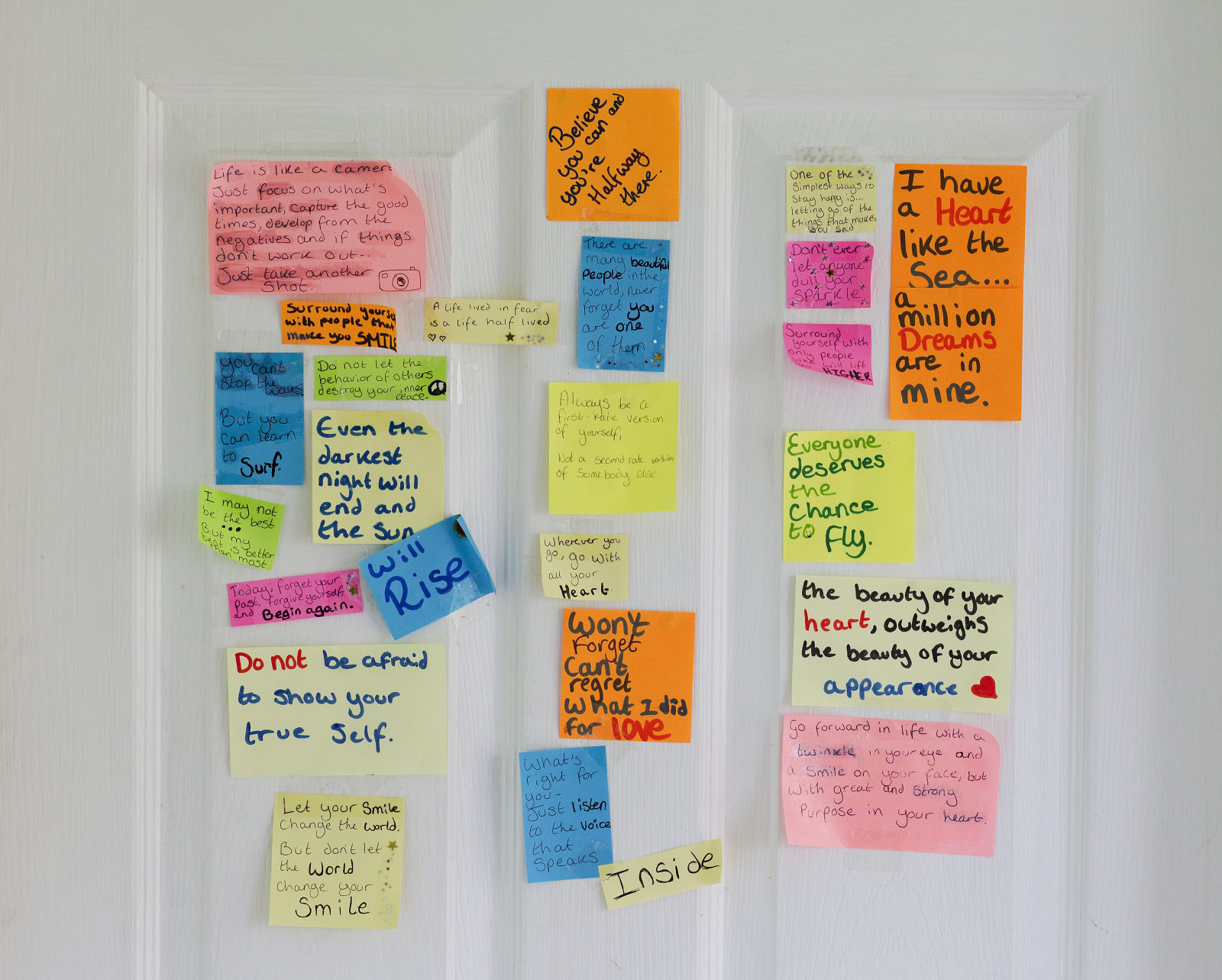

Vinay, 16.

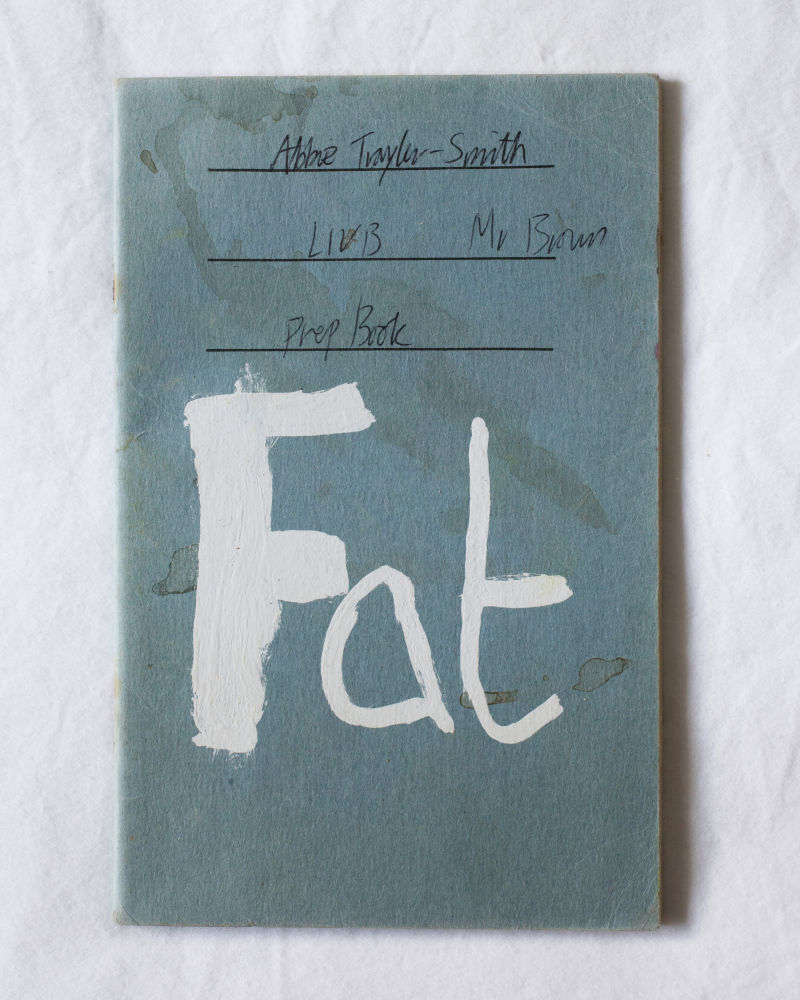

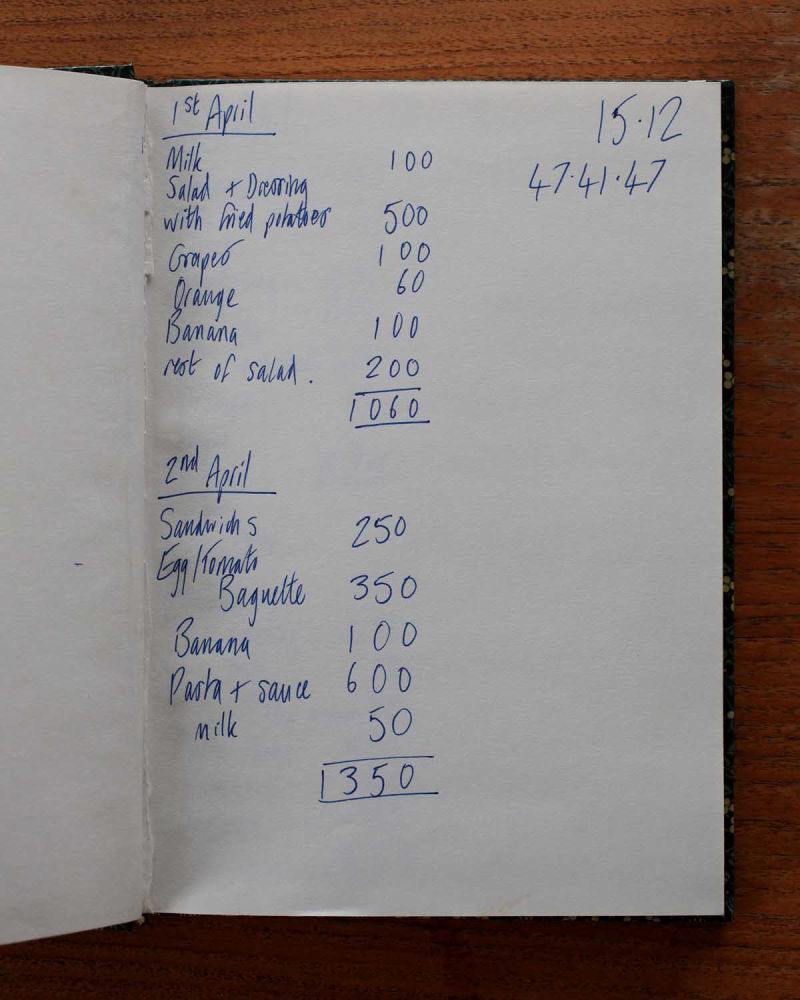

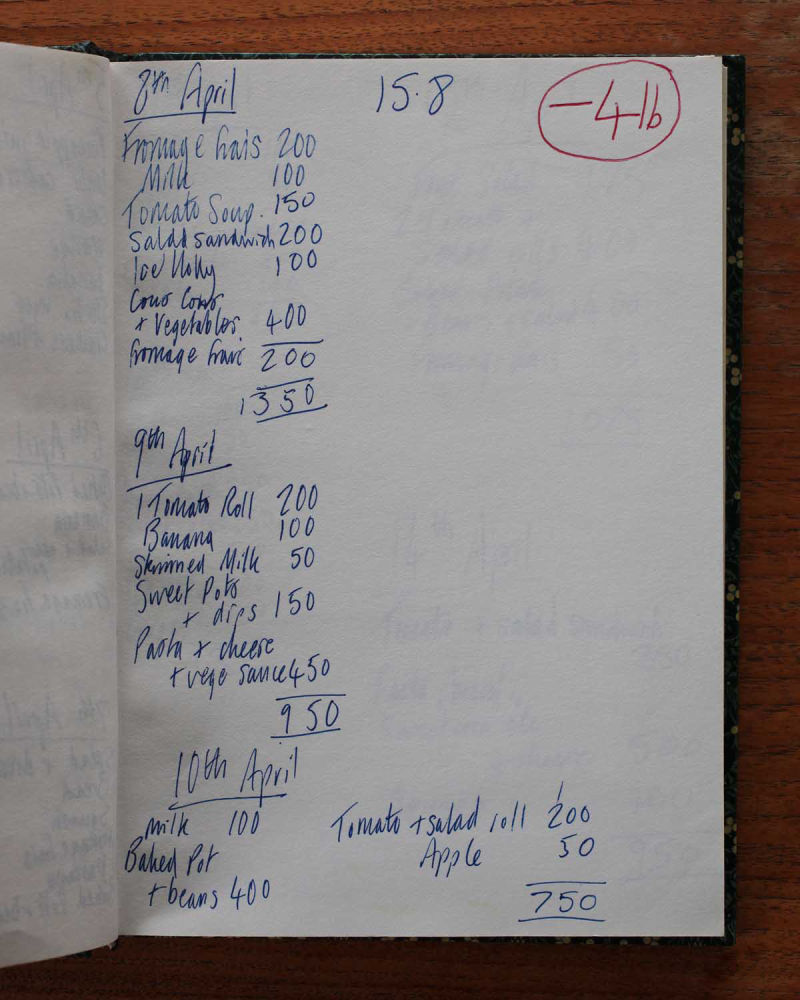

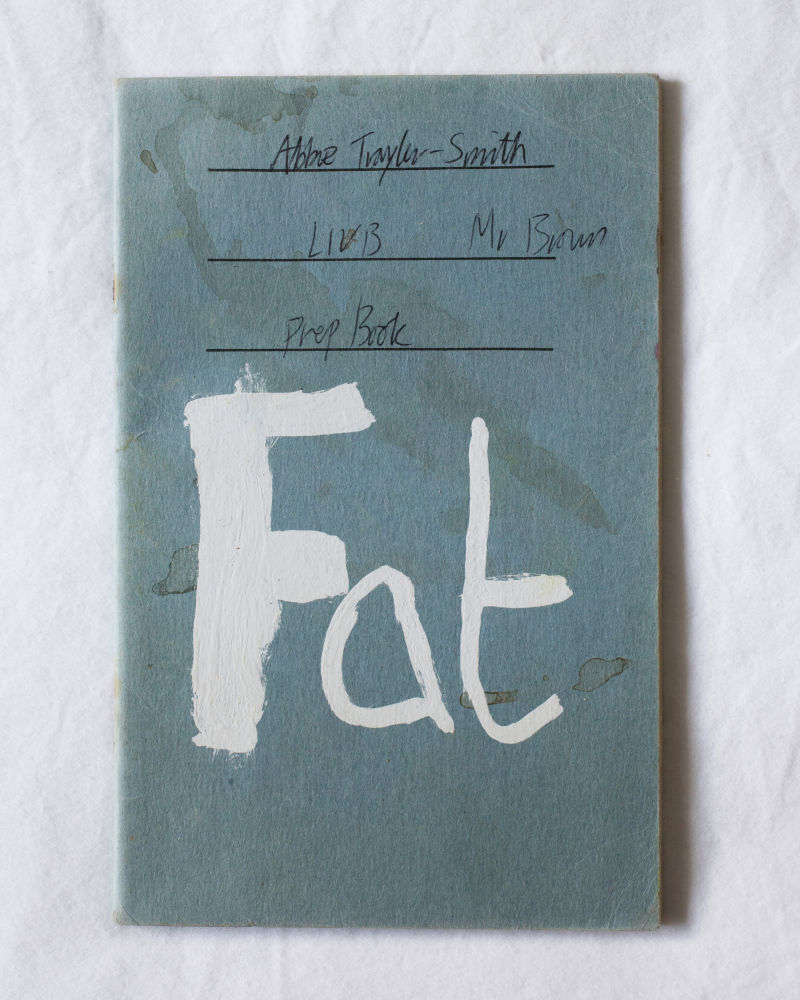

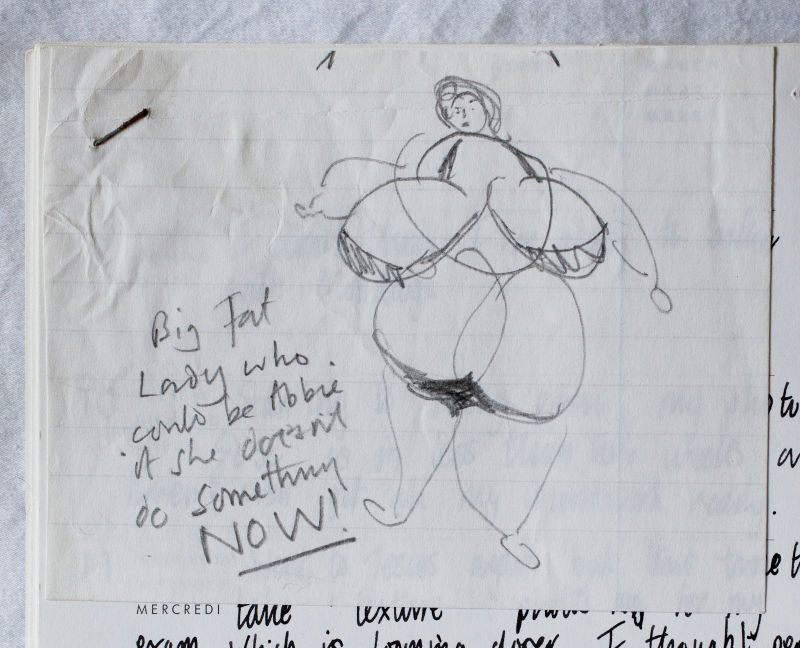

Vinay, 16. My schoolbook from 1990 when I was 13.

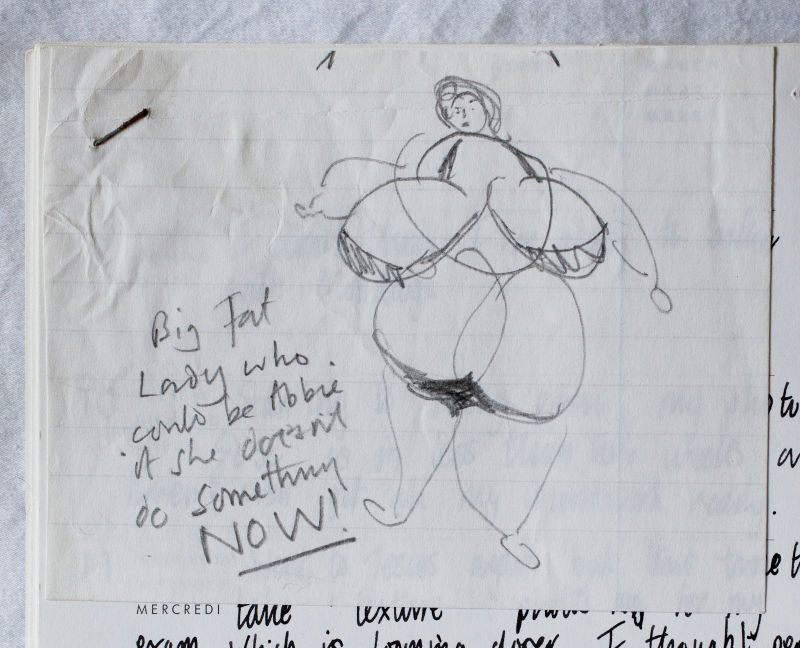

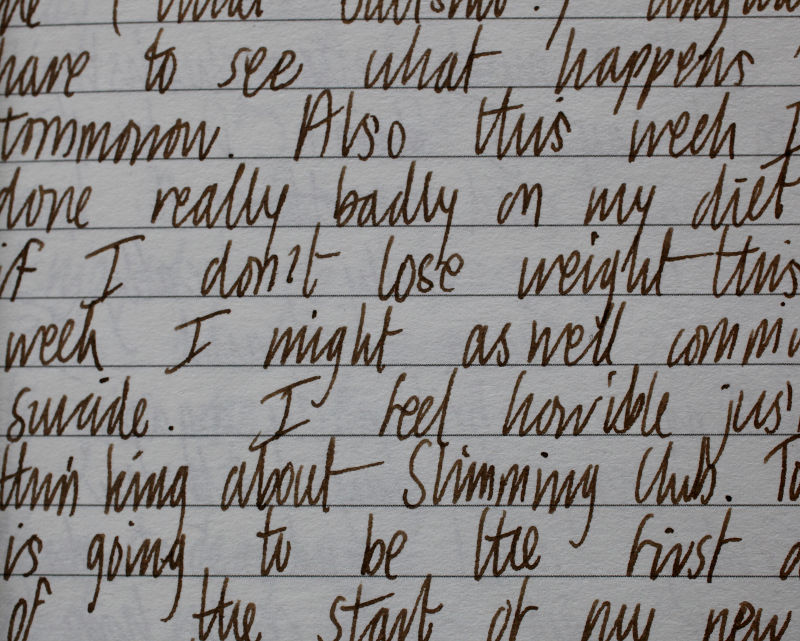

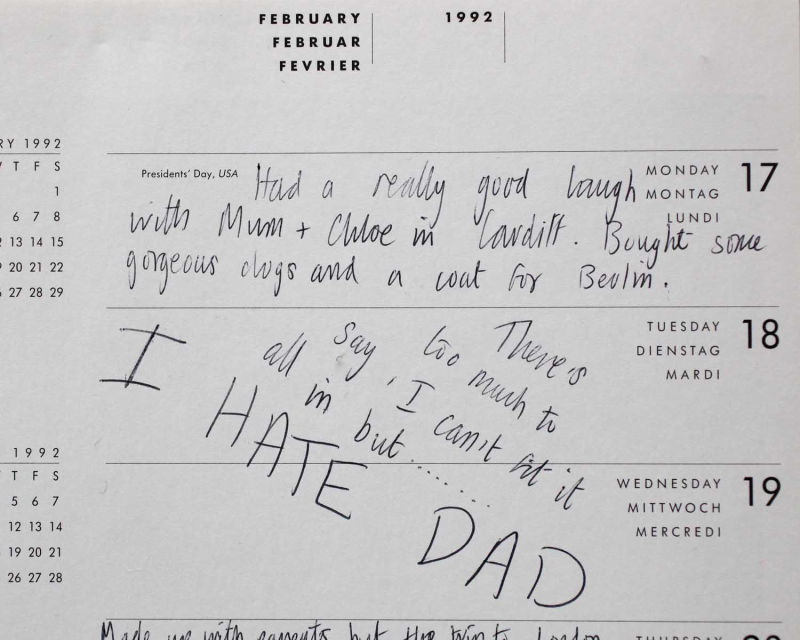

My schoolbook from 1990 when I was 13. A note my dad left for me, which I stapled in my diary from 1992 when I was 14.

A note my dad left for me, which I stapled in my diary from 1992 when I was 14. Chelsea, 17.

Chelsea, 17.